books

Image Takers Image Makers,

Thames & Hudson 2007

Identifications D’une Ville,

Editions du Regard 2006

PLATFORM 1998-2006,

ed Sheila Lawson, Platform 2006

Surface, Contemporary Photographic Practice,

Booth Clibourne Editions 1997

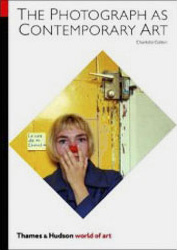

The Photograph as Contemporary Art,

Charlotte Cotton, Thames & Hudson 2004

catalogues

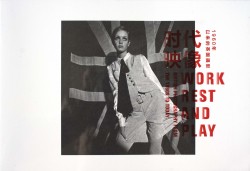

Work, Rest and Play – British

Photography from the 1960’s to Today,

The Photographer’s Gallery 2015

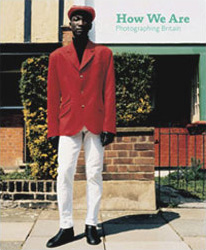

How We Are: Photographing Britain,

Tate Britian 2007